Matthew concludes his genealogy of Jesus by covering the period from the Exile event to the birth of the Messiah. This section emphasizes Jesus’s role as the Messiah.

There is no apparent parallel account for this genealogical record in the Gospels.

The deposed king Jeconiah grew up and lived his days exiled in Babylon. One of his sons was Shealtiel. Matthew tells us that Shealtiel was the father of Zerubbabel. The vague language of 1 Chronicles 3:17-20 suggests that Shealtiel was likely Zerubbabel’s grandfather. Matthew tells us that Zerubbabel descended from Shealtiel. Zerubbabel’s father was Pedaiah. Pedaiah is left unnamed by Matthew, but he is listed in 1 Chronicles.

Zerubbabel is identified as one of the leaders who returned to the land of Israel from the deportation to Babylon in Ezra 2:2. After his return he helped lead the efforts to rebuild the temple. (Ezra 3:8-Ezra 6) Haggai 1:1 says that Zerubbabel was governor of Jerusalem.

Zerubbabel is the last figure in Matthew’s genealogy of Jesus who is mentioned in the Old Testament. There is little history recorded in the Old Testament after the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. There was a gap of approximately four hundred years in which no scripture was given by God prior to the advent of Jesus the Messiah.

Matthew’s genealogy of the Messiah runs not through Mary (as in the Gospel of Luke), but through Joseph, Mary’s husband. Joseph took and raised Jesus as his son. But Joseph’s seed did not impregnate Mary. God’s Spirit did. Unlike every other man in Jesus’s lineage who fathered a son, Matthew masterfully points out that Joseph is only the husband of Mary, the woman by whom Jesus was born. In so doing Matthew’s genealogy beautifully emphasizes for his Jewish audience both the Divine and Human natures of Jesus. Jesus was both eternal God and born of a woman. He is a “son of Abraham,” a rightful king in the line of David, and the foretold Messiah come to set his people free; but at the same time, He is also God.

As Matthew emphasized David’s title as king in verse 6, so too does Matthew emphasize Jesus’s title as Messiah in verse 16. Messiah means “Anointed One” and is often translated as “Christ” throughout the New Testament. In the Old Testament there were many different people “anointed” for different offices or tasks. King and priest were the offices most frequently associated with being anointed. In a sense there were many anointed ones throughout Jewish history, but only one anointed to the office of both king and priest forever over Israel (Hebrews 7).

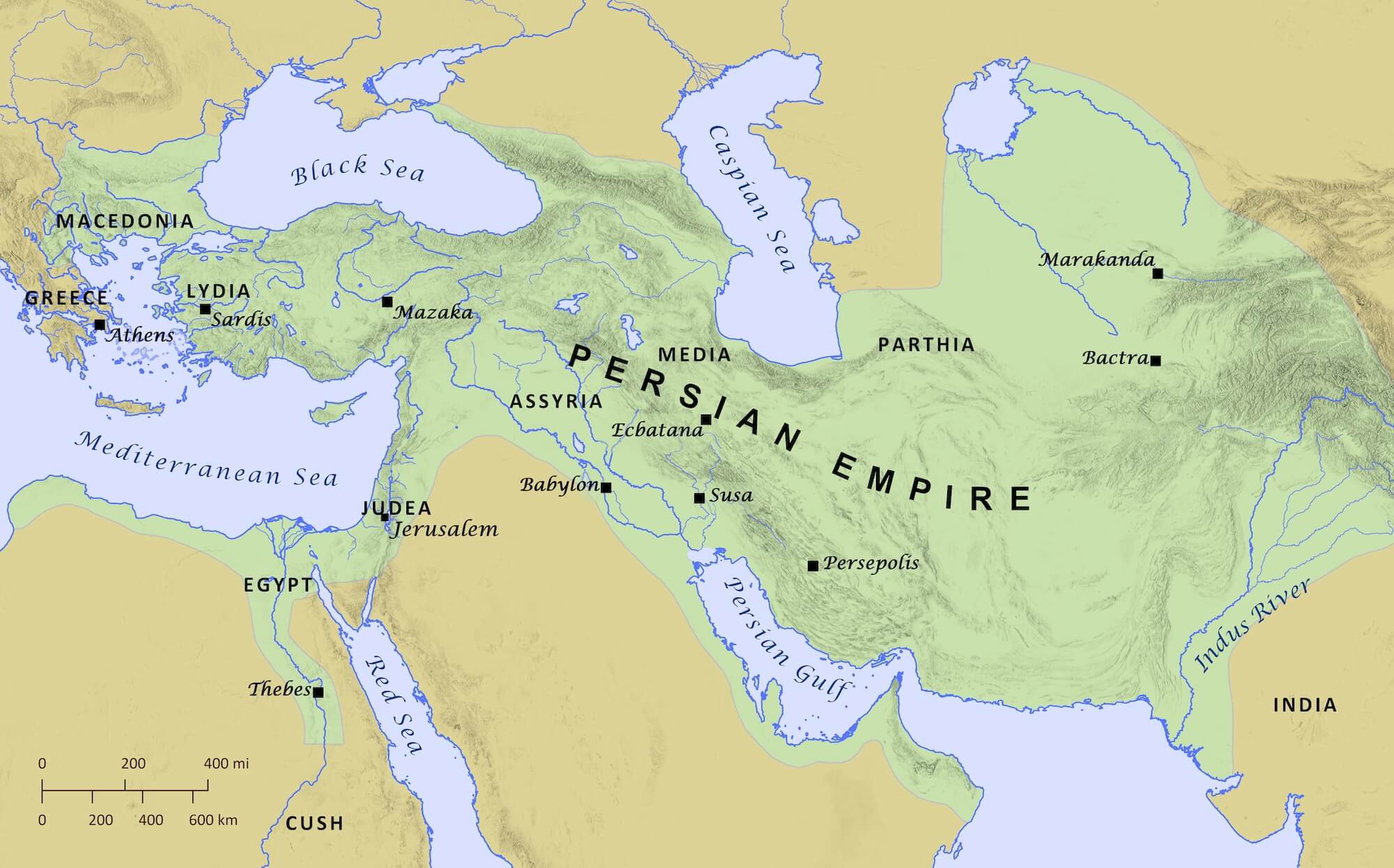

Aaron and his sons were anointed in Exodus 29. David was anointed as King by the prophet Samuel. The prophet Isaiah even declared that Cyrus, the Persian King, was anointed by God to a specific task (Isaiah 45:1). All of these anointed people were a foreshadowing of the Messiah. After the fall of Jerusalem and the deportation to Babylon, Jeconiah was the last rightful heir of David to occupy the throne. Most of Judah was deported to Babylon. They remained in exile there until some began to return under Ezra (Ezra 1:1-4). After the end of the political Kingdom of Judah the Jews endured the oppression of multiple foreign powers. No king sat on the throne after the return from Babylon.

Judah became a vassal of Persia, who had conquered Babylon (Daniel 5:30-31). It then became a vassal of Greece, after Alexander the Great conquered Persia. The Jews had a period of self-rule under the Maccabees, after the Maccabees led a revolt against the Seleucid kingdom; one of the four kingdoms that broke off from Alexander the Great’s empire. Judah then fell under the rule of Rome.

During this period where Judah was primarily under oppression from foreign rulers and fueled by prophecies of the coming Messiah throughout the Old Testament, the Jews began to intensely yearn and hope for a political Messiah to rescue them from foreign rule. Throughout his Gospel, and here at the end of his genealogy, Matthew demonstrates and declares Jesus to be the Messiah. Jesus is the Kingly Messiah, who will usher in His Kingdom and set His people free. However, the Messiah’s kingdom will first be a kingdom of spiritual freedom, which runs counter to what was expected. This is the root of why even Jesus’ twelve disciples continually fail to understand Him. He is the King of the Jews, but He disappointed their common expectations.

Even though Jeconiah was the last rightful heir to sit on the throne of Israel, David’s kingly line continued as God promised to him in 2 Samuel 7:16, “Your house and your kingdom shall endure before Me forever; your throne shall be established forever.” Matthew traces David’s royal line from Jeconiah to Joseph. Matthew continues from Jeconiah to Shealtiel, Zerubbabel, Abihud, Eliakim, Azor, Zadok, Achim, Eliud, Eleazar, Matthan, and all the way to Joseph’s father Jacob.

There is an interesting twist concerning the children of Jeconiah found in 1 Chronicles 3:17: “The sons of Jeconiah, the prisoner, were Shealtiel his son,” and then the text names other offspring of Jeconiah and their children’s children, but says nothing of Shealtiel’s offspring. Ezra 3:8 tells us that Zerubbabel, who became Jerusalem’s governor during the return from exile, was Shealtiel’s son, but nowhere in the Old Testament is there mention of Zerubbabel’s descendants. Perhaps this omission foreshadows the kingly line falling into obscurity. Another reason Shealtiel’s descendants might be left unnamed in the Old Testament when the other sons’ descendants are named is to protect them from being targeted for elimination by Israel’s rulers. If this were the case, it would allow the royal line to continue in secret, without the occupying forces knowing about it until an opportune moment.

At any rate, the Old Testament draws to a close with these events and therefore no additional names can be discerned from the scriptural records. Shortly after the return (Zerubbabel’s generation), Israel underwent a period of roughly 400 silent years, where no scripture was written.

From the historical events recorded in Nehemiah and the prophetic utterances of Malachi there is no biblical record of prophets who spoke on behalf of God until John the Baptizer appeared.

Biblical Text

12 After the deportation to Babylon: Jeconiah became the father of Shealtiel, and Shealtiel the father of Zerubbabel. 13 Zerubbabel was the father of Abihud, Abihud the father of Eliakim, and Eliakim the father of Azor. 14 Azor was the father of Zadok, Zadok the father of Achim, and Achim the father of Eliud. 15 Eliud was the father of Eleazar, Eleazar the father of Matthan, and Matthan the father of Jacob. 16 Jacob was the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, by whom Jesus was born, who is called the Messiah.

Check out our other commentaries:

-

Exodus 4:1-9 meaning

Moses’ third objection deals with unbelief on the part of the Israelites. “What if they do not believe me?” seems to be the issue. The...... -

Psalm 27:1-3 meaning

Placing one’s trust utterly in the Lord for all of life’s experiences results in a deeper understanding about life, the good as well as the...... -

Hosea 7:8-12 meaning

The LORD describes Israel’s ignorance and vulnerability due to her pride. The nation has become like a senseless dove, flitting back and forth between trusting...... -

Acts 9:36-43 meaning

There is a believer in the coastal city of Joppa named Tabitha. She is well known to be charitable and kind. But she falls ill...... -

Acts 2:37-41 meaning

Some of the Jews are ashamed that they put God’s messiah to death. They ask Peter what to do, and he calls them to repent......