Bearing the Cross: Exploring the Unimaginable Suffering of Crucifixion

Throughout the annals of human history, few forms of execution have captured the collective imagination and invoked horror as profoundly as crucifixion. Originating in ancient Rome, this brutal and agonizing method of capital punishment was reserved for slaves, non-citizens, and enemies of the state. It served as a stark and vivid warning to not challenge Roman supremacy. The process of crucifixion, characterized by its excruciating pain and degrading humiliation, was meticulously designed to shock onlookers and terrorize potential wrongdoers from causing mischief.

Crucifixion transcended the realm of mere execution. It was a potent tool of social control employed by the Roman Empire over the people it conquered. This merciless form of punishment was not only a means of dealing with offenders but also a strategic deterrent against potential wrongdoers. The Romans believed that by making the process of crucifixion agonizingly public, they could instill an overwhelming sense of dread, discouraging individuals from committing lawlessness, lest they too suffer this agonizing end.

Crucifixion effectively stigmatized rebellion. The Roman poet, Quintilian, contributed a chilling perspective. He asserted, "The very word 'cross' should be far removed not only from the person of a Roman citizen but from his thoughts, his eyes, and his ears" (Quintilian. "Institutio Oratoria" 9.4.14). Quintilian's statement reveals the societal horror that crucifixion evoked—a term that was synonymous with terror and shame.

Given its horrors, Quintilian's opinion about the cross was understandable and completely reasonable. It undoubtedly was a perspective shared by most everyone. But this common dread of the cross makes one of Jesus's teachings that is frequently quoted in the Gospels all the more radical and baffling,

"And He was saying to them all, 'If anyone wishes to come after Me, he must deny himself, and take up his cross daily and follow Me. For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for My sake, he is the one who will save it.'"

(Luke 9:23-24 - See also Matthew 10:38, 16:24, Mark 8:34)

It is a testament to the power of the Gospel that what was once the emblem of suffering and shame has become the cultural symbol of eternal life in Jesus.

While each of the Gospels detail Jesus's death on the cross, none of them describe the tortures or process of crucifixion itself. This was likely because their primary readers would have been all too familiar with the systematic brutality of this method of execution. They simply had no need to explain it. Instead, the Gospels focus on:

- aspects of Jesus's crucifixion which fulfilled various prophecies concerning the Messiah;

- the way He was rejected and mocked by the Jews;

- the things Jesus said as He was being crucified;

- and the supernatural events that marked His death.

But for those of us who live in an age and/or culture where crucifixion is not a form of execution, it is difficult to imagine the pain, suffering, and humiliation that Jesus endured in obedience to His Father and out of His love for the world He died to save.

This Bible Says article will explain the cruel process of Roman crucifixion in light of the agonies and humiliation Jesus suffered.

The process of crucifixion was a carefully orchestrated ordeal that blended the art of punishment with the science of suffering. It was a series of calculated steps, each amplifying the victim's agony, maximizing their humiliation, in an attempt to showcase their submission to Roman authority. But in the end, the cross, which was to meant to be the painful end of Jesus, became His greatest triumph when He came back to life. As was the case with His predecessor Joseph, what man intended for evil, God meant "for good in order to… preserve many people alive" (Genesis 50:20).

The Cross

The Roman Empire used four basic types of crosses.

- "Crux Simplex"

The first type of cross was shaped like an "I." It consisted of a simple vertical beam. The victim's wrists were crisscrossed and nailed above his head. The victim's feet were nailed slightly above a crude wooden platform which was provided so that he could push up for air and thus cruelly delay death as he hung on the cross. Recent archeological evidence shows that the Romans sometimes nailed each ankle separately on either side of the beam.

- "Crux Commissa"

The second type of cross was shaped like a "T." It is sometimes called the "Tau cross" because it resembled the upper case Tau in the Greek Language. "Crux Commissa" means the "connected cross." Its victim's wrists were stretched wide and nailed on either end of the cross beam. The victim's feet were nailed in a similar fashion to the Crux Simplex, the "I"-shaped cross.

- "Crux Immissa"

Often called the "Latin Cross," the third type of cross was shaped like a "t." It is the most iconic because this version is most often used in depictions of Jesus's death. "Crux Immissa" means "inserted cross." The victim's hands were stretched out and nailed to the horizontal beam (called the patibulum). His feet were nailed to the vertical beam (called the stipes) in a similar fashion to the previous two types of crosses.

- "Crux Decussata"

The fourth type of cross the Romans used was shaped like an "X." It resembles the Roman numeral X ("deca" or "ten"); hence the name "Decussata." Here the victim's hands and feet were stretched diagonally in each direction and nailed accordingly.

Which type of cross was Jesus crucified on?

The Gospels do not say. They simply say: "when they had crucified Him" (Matthew 27:35); or "they crucified Him" (Mark 15:24, Luke 23:33, John 19:18). Church tradition suggests that it was the third type - the Crux Immissa, or "t" shaped cross. And Matthew provides information that suggests that traditional account was correct when he writes: "And above His head they put up the charge against Him which read, 'THIS IS JESUS THE KING OF THE JEWS'" (Matthew 27:37).

The charge was written on what was called a "titulus." The only types of crosses where it could have been placed above Jesus's head as Matthew reports are the first and third types of crosses—1. "Crux Simplex," "I" cross; or 3. "Crux Immissa," "t" cross. Further supporting the traditional perspective is the fact that the crux simplex was primarily utilized in Italy. Therefore it is most likely, but not certain, that Jesus was executed on a "t"-shaped cross as is generally depicted of Him.

The Place of Crucifixion

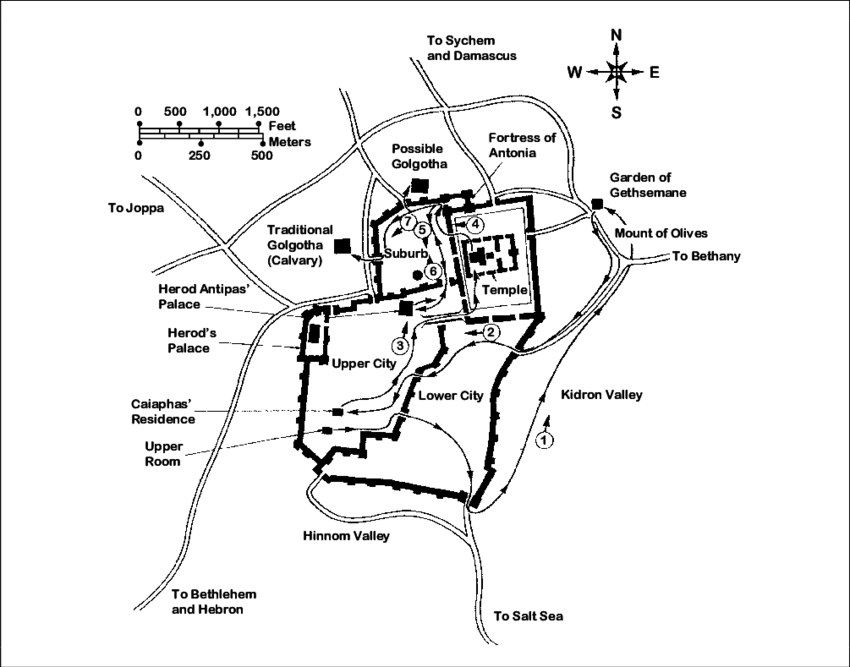

Crucifixions were messy affairs, and consequently were conducted outside the city. But because they were used as tools to psychologically intimidate and terrorize would-be criminals, they were usually done along the road or near a city gate to maximize the number of people who could witness its horrors.

Such was the case with Jesus, who was crucified by the city gate (Hebrews 13:12). The Gospels indicate that He was along the road where "those [who were] passing by were hurling abuse at Him" (Matthew 27:39). Jesus was crucified on Passover, when the population of Jerusalem swelled to a million or more Jews, this transformed Jesus's humiliating death into a national spectacle.

The Gospels call the place where Jesus was crucified "Golgotha" or "Place of the/a Skull" (Matthew 27:33, Mark 15:22, Luke 23:33, John 19:17).

The term "Golgotha" is an Aramaic word. Aramaic was the common language used by the Jews in the first century A.D.

To learn more, see The Bible Says article: "The Four Languages of Jesus's Judea."

Matthew explains Golgotha's meaning as "Place of a Skull." The Latin word with this meaning is "calva" from which the English term "Calvary" is derived. Therefore, the Aramaic term "Golgotha" and the English term "Calvary" have the same meaning.

The likely reason this place was called Golgotha, or Place of a Skull, was because of the awful executions which regularly occurred there during the Roman occupation. Some have also suggested that it was called this because the landscape appeared to resemble a skull—perhaps it was called what it was for both reasons.

The naming of Golgotha in this manner is similar to the naming of other places which were named after the activity that took place there. For instance, inlets that are named "Pirate's Cove" are given this name, not because they are shaped like a pirate ship, but rather because they were a haven for pirates.

Two locations have been proposed as the place where Jesus was crucified.

One is the the traditional location, where the Church of the Holy Sepulcher now stands, the other is a place called "Gordon's Calvary."

This article favors the traditional site. The traditional location was between two gates and just outside the existing city wall at the time Jesus lived. And it was the place the early church recognized as Jesus's crucifixion site. In a twist of historical irony, the Roman Emperor Hadrian had a temple dedicated to Venus erected at this location to dishonor Christians who venerated it as the place where Jesus was crucified, thus unintentionally preserving its location for posterity. Two centuries later, after the Emperor Constantine adopted Christianity as the official religion of the Empire, his mother had the pagan temple destroyed and a church built and dedicated in its place. This structure has been destroyed and rebuilt several times since, but the location has remained the same.

Gordon's Calvary was first proposed as the site of Jesus's crucifixion in 1842 as an alternative site by Otto Thenius. British General Charles Gordon brought widespread attention to Thenius's proposal and popularized this location in the 1880s. Gordon's Calvary is found north of Jerusalem, less than a quarter mile from the "Fish Gate."

The Crucifixion Procession

The journey toward crucifixion often began with the Roman executioners forcing their victims to carry their own cross to the place where they were to be crucified.

One second century writer mentions this custom in an off-hand comment: "The person who is nailed to the cross first carries it out" (Artemidorus of Daldis, Oneirocritica," Book 2, Section 6, Fragment 5).

Victims sometimes carried only the horizontal crossbeam or "patibulum" which would be fastened to the vertical cross at the execution site. Sometimes they carried a formed cross.

Forcing the condemned to carry their cross not only served to physically exhaust the individual but also symbolized their impending humiliation. Carrying the instrument by which they would be tortured was a way to publicly compel them to submit to their defeat and the supremacy of Rome as they stooped and stumbled along in a submissive, vulnerable position.

The Greco-Roman historian, Plutarch, also observed the ironic rationale for this protocol, "every criminal who goes to execution must carry his own cross on his back, vice frames out of itself each instrument of its own punishment" (Plutarch. "De Moralia: On the Delays of Divine Vengeance." Section 9). As the criminal carried his cross, the crowd was encouraged to jeer the criminals, others gaped or looked away in horror. It was a burdensome and lonely road to their death.

Psalm 22, written a thousand years before Jesus was born, prophetically describe the Messiah's suffering and death in a crucifixion-like manner. Psalm 22:6 foretells of the Messiah's humiliation: "But I am a worm and not a man, A reproach of men and despised by the people."

The Gospel of John plainly states that Jesus was bearing "His own cross" when He went out with the executionary party from the Praetorium (John 19:17). But it is not clear if Jesus was forced to carry a patibulum or His entire cross.

Along the way the Roman Legionnaires who were assigned the task of crucifying Him recognized that He was unable to carry His cross. This was because He had previously been scourged by order of Pilate, as the governor attempted to mollify the crowd's demands for Him to die. His body was severely weakened from the shock of pain and blood loss from this scourging. The soldiers coerced Simon of Cyrene, "a passer-by coming from the country" (Mark 15:21) to carry His cross instead.

Nailing and Raising of the Cross

Once at the execution site, the macabre ballet continued.

If the victim was not forced to carry his cross naked, he was usually stripped of his clothes before being nailed to the cross. The purpose was that the victim would be stripped of all dignity and be crucified naked.

Jesus was wearing His own clothes on the way to Golgotha (Matthew 27:31, Mark 15:20), but had them taken off Him before He was crucified (Matthew 27:35, Mark 15:24, Luke 23:34b, John 19:23-25a). Per Roman custom, He was probably crucified completely naked.

The victim's limbs were then extended across and nailed to the cross. This peculiar posture—arms outstretched, legs bent—was designed to maximize both the pain and the struggle for breath, creating a torturous rhythm.

Arms were splayed along the horizontal patibulum. Nails were driven through the wrists, between the ulna and radius, the two bones that make up the forearm. These bones were large enough to support the weight of the victim's body. (The bones in the hand would not be strong enough to do this in most cases). The place where the nails were driven through was directly into the median nerve which travels from the elbow to the hand. This caused sharp pain that shot up the victim's arm. The convulsions they caused were excruciating.

For this reason, one of the few merciful acts the executioners sometimes offered to their victims was to have them drink wine mixed with gall as an anesthetic concoction, before the nails were driven through. The soldiers who crucified Jesus showed Him this mercy, but after tasting it, Jesus "was unwilling to drink" it (Matthew 27:34). Apparently, Jesus wanted to have His full wits about Him as He endured the agonizing trial of His death.

If the patibulum (horizontal beam) was not previously connected to the stipes (vertical post), then it was hoisted up at this time and fastened to the stipes while bearing the weight of the criminal nailed to it. Once erected, the feet were positioned and nailed. If the patibulum was already connected to the stipes, the victim's feet were nailed prior to the raising of the cross.

When the victim's legs were nailed to one of the first three types of crosses ("I," "T," or "t") then the feet were either nailed slightly above the wooden platform, or they were nailed on either side of the vertical beam of the cross, just above the ankle between the tibia and fibula bones. (If the cross was an "X" shape, the feet were likely turned outward before they were nailed. In most cases, the nails were driven through the fibular nerve which is a branch of the sciatic nerve originating in a person's lower back. Once again, the pain would be severe as it shot up the victim's leg and through their back.

Jesus's nailing to the cross fulfilled Isaiah's prophecy concerning the Messiah's suffering: "But He was pierced for our transgressions" (Isaiah 53:5). Remarkably this prophecy was given hundreds of years before crucifixion was invented.

Psalm 22 was written centuries before Isaiah; it too describes the Messiah's suffering that correspond to the crucifixion: "They pierced my hands and my feet" (Psalm 22:16).

As the cross was raised, the victim's full weight pressed down upon the nails driven between his wrist bones. As the cross settled into the earth or the patibulum was fastened to the vertical post, the victim experienced an agonizing and heavy jolt that violently jarred his body and often pulled bones out of joint.

As Jesus suffered this the prophecy in Psalm 22 was fulfilled: "And all my bones are out of joint" (Psalm 22:14).

Luke's chronological account of Jesus's life indicates that it was either while the soldiers were driving the nails through His wrists and/or raising His cross that Jesus repeatedly prayed: "Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing" (Luke 23:34).

Agonizing Struggle and Prolonged Suffering

Breathing, the most basic of human actions, became a battlefield of agony for the crucified. The combination of constriction from the victim's own weight and the awkward posture made every act of inhaling an act of torment. To inhale, the victim had to push up with their legs and pull up with their arms. Bones grinded against the nails. Muscles strained and cramped. The victim's back scraped against the course wood and quickly rubbed the skin raw. The victim could hold himself up for air, but soon his tired muscles gave way and he had to relent. If he dropped his weight at once, his full weight would be painfully caught by the nails in his wrists and feet. Lowering himself slowly required more energy, which gradually depleted every time this cycle repeated itself.

Time itself seemed to twist and stretch during crucifixion. The duration of the ordeal varied—hours, days, or even more—depending on factors such as the victim's health, the chosen form of crucifixion, and the whims of the executioners. The prolonged exposure to the elements—scorching sun, biting wind, or drenching rain—further compounded the torment, fostering dehydration and exacerbating physical distress.

Seneca the Younger, a stoic philosopher and Roman senator, accurately described the suffering of the cross in his rhetorical questions: "Can anyone be found who would prefer wasting away in pain dying limb by limb, or letting out his life drop by drop, rather than expiring once for all? Can any man be found willing to be fastened to the accursed tree?" (Seneca. "Consolation to Helvia" 17.4).

The human body's response to crucifixion was a symphony of torment. The nails driven through the wrists or hands triggered excruciating pain, as they pierced nerves and bones. The strained posture and the ceaseless battle for breath led to physical exhaustion, shock, and the desperate yearning for relief. The victim's body bore the weight of its anguish, exhibiting a range of harrowing responses. Among the most common disorders were:

- Hypovolemic Shock

Hypovolemic shock is a state where the body lacks sufficient blood to function properly.

Blood loss was an inevitable consequence of the crucifixion process. Blood seeped from the wounds caused by the nails, while the trauma inflicted on the body triggered this condition. This condition manifested as a racing heart, plummeting blood pressure, and a disorienting haze.

- Suffocation and Asphyxiation

Crucifixion was designed to slowly suffocate its victims by their own weight. Asphyxiation is the medical condition that results from suffocation. It is characterized by a lack of oxygen supply to the body's tissues and organs, often resulting from the inability to breathe adequately.

Breathing, a reflex we often take for granted, became an agonizing struggle during crucifixion. The combination of the awkward posture and the constriction of the chest and diaphragm made inhaling a Herculean task. To draw breath, the victim had to exert tremendous effort, pushing up with their legs to expand their lungs. This action, while allowing a gasp of air, meant scraping their wounded back against the unyielding wood. Exhaling was equally distressing, as relaxing the legs intensified the torment in their wrists or hands.

- Dehydration and Exposure

Dehydration is a condition that occurs when the body loses more fluids, primarily water, than it takes in. This imbalance can lead to a decrease in the body's ability to function properly, resulting in symptoms such as thirst, dry mouth, fatigue, and muscle cramps.

The prolonged duration of crucifixion, frequently carried out in open and vulnerable locations, exposed the victim to the capriciousness of the elements. Under the unrelenting sun or during merciless rains, dehydration became a constant companion. This dehydration magnified the victim's pain, as their tissues suffered under the strain, and the thirst, an unquenched longing, became a persistent torment.

These agonies of crucifixion were unrelenting. All three of these disorders worked in cruel concert together to increasingly intensify each condition. During the hours or days a victim remained on the cross, the relief of death seemed tantalizingly near and yet was constantly out of reach until at long last the body gave way.

Jesus suffered all three disorders on the cross.

Before He even arrived at Golgotha, Jesus was experiencing severe blood loss and hypovolemic shock from the scourging Pilate gave Him. This is seen in the Roman soldiers coercing of Simon of Cyrene to carry Jesus's cross for Him (Matthew 27:32), as He was physically unable to do so. The disorder of hypovolemic shock may have contributed to the blood-and-water mixture pouring out of Jesus when the Roman soldiers stabbed His side after He had already died (John 19:34). Psalm 22 poetically described the effects of the cross and hypovolemic shock upon the Messiah's heart when it says: "My heart is like wax; It is melted within me" (Psalm 22:14).

Even though the Gospels do not record instances of Jesus experiencing asphyxiation or suffocation—these conditions were universally endured by those who were crucified. In other words, to be crucified meant to be suffocated and deprived of oxygen.

The Gospels do describe the dehydration Jesus suffered. Among the seven statements He gave on the cross was the simple short comment: "I am thirsty" (John 19:28). Someone offered Him wine and gave Him a drink to alleviate this suffering (Matthew 27:48, John 19:28-29a).

Psalm 22 seems to have predicted the Messiah's dehydration when it says: "My strength is dried up like a potsherd, And my tongue cleaves to my jaws" (Psalm 22:15).

Even as Jesus suffered greatly and was executed on a Roman cross, He did not die until He gave up His Spirit,

"And Jesus cried out again with a loud voice, and yielded up His spirit."

(Matthew 27:50)

"And Jesus, crying out with a loud voice, said, 'Father, into Your hands I commit My spirit.' Having said this, He breathed His last."

(Luke 23:46)

"Therefore when Jesus had received the sour wine, He said, 'It is finished!' And He bowed His head and gave up His spirit."

(John 19:30)

From Torture to Triumph

Returning to the Roman Senator Seneca's question—"Can any man be found willing to be fastened to the accursed tree?" (Seneca. "Consolation to Helvia" 17.4)—we reply: "Jesus" who willingly laid down His life for the sins of the world to please His Father (Isaiah 53:10-12, Matthew 20:28, Luke 22:42, John 10:17-18, Philippians 2:6-8).

The reason Jesus did this seemingly unreasonable thing was for the joy set before Him by His Father in Heaven (Hebrews 12:2). Compared to that joy, all the pain and suffering of the cross was despised as nothing.

In Christ Jesus, a similar opportunity awaits us—if we have the faith to despise our trials and hardships, to set our minds on the things above, and to overcome all that we face by relying on God's grace (Romans 8:17-18, 2 Corinthians 4:17, Colossians 3:2, 2 Timothy 2:11, Hebrews 12:1, 1 Peter 1:6, Revelation 3:21).

When it comes to our own suffering, whatever it may be, we are called to have the same mind, or perspective, as Christ (Philippians 2:5). If we are willing to lose our life for His sake by taking up our cross daily and following Him, we will find life in the fullest (Luke 9:23-24).

Christ's paradoxical statement to take up our cross (Luke 9:23-24) is an invitation and an exhortation.

As an invitation, Jesus's paradoxical statement to take up my cross means to bear the responsibility of my own death—the death that leads to life. God never forces anyone to follow Him. He gives us free will and the ability to decide whether we will do what we want or surrender our will to God's. We choose whether we will cling to our plans, which inevitably pass away, or follow Jesus through suffering into His kingdom which cannot be shaken (Hebrews 12:28-29). Jesus invites us to true fulfillment and the abundant life by surrendering; putting to death; literally crucifying every ambition, desire, agenda, or dream that does not align with His will for our life.

Jesus gave us this example in the Garden of Gethsemane (Luke 22:42). To accept His invitation often requires a radical change in our perspective about what we think is best. It requires faith to see and choose this perspective. But when we see our lives as God sees them, then we joyfully embrace the sufferings for the life they produce (Matthew 13:44, 19:27-29).

Christ's paradoxical statement is also an exhortation. Just as each person is uniquely created by God, we are each destined and called and equipped to perform different tasks for God's kingdom (Ephesians 2:10). The exhortation to take up your cross daily (Luke 9:23-24) is a call to go all the way to the point where you have finished your assignment as Christ finished His task (John 19:30). It is an exhortation to fulfill our destiny in this life, in this day, in this moment.

© 2024 The Bible Says, All Rights Reserved. | Privacy Policy